Freefall: In conversation with photographer Alexander Treves

- Yasmin Turner

- Dec 6, 2022

- 8 min read

UK-born Alexander Treves has worked in finance for over two decades, and has moved countries seven times with his job. Between his day job and family life, Alexander has travelled the world photographing scenes that show a different perspective to the usual traveller’s narrative. With photographs taken across a time frame of eight years, his new photo book Freefall reveals how the lives of people globally are affected by violent conflicts and persecution.

We spoke to Alexander to find out more about his motivations for creating Freefall, how he chose the locations included in the book, and his personal insights from the project.

Your new photo book, Freefall, documents refugees and displaced people whose everyday lives have been upended by war or persecution. Why did you choose to do this project?

By way of background I’ve moved country several times and I've got a history of art degree. I’m interested in photography as a way of documenting things. I’ve moved from London to Singapore, back to London, then Tokyo, then Bombay, then back to Tokyo, then Hong Kong and now I'm in Singapore.

When I was living in India, I thought that a lot of the photography of the country was really quite shallow and wrong. I think when many people imagine a photograph of what goes on in India, they might picture a woman in a very colourful sari with big hoop earrings. I believe that’s a really reductive way of understanding what life is like in India for a lot of people.

About 10 million people in Bombay live in slums. It’s not to say that's life for everyone, but life for a lot of people is quite tough and that cliché of colour and vibrancy and “it's okay to be poor as long as you're smiling” - I think is a misrepresentation.

So I tried to take photographs of the parts of India that - while not representative of everyone - were taking a different perspective. I managed to take pictures of people shooting up heroin or smoking heroin, I took pictures in an abattoir, I took pictures of people who were really on the margins of society, not because I think that's the whole story about India but it's a part of the story which I don't think is adequately represented in photography.

However an issue is that I was documenting things that I thought were important to document, but I worried there was quite a voyeuristic element which I was uncomfortable with. I was photographing other people’s difficulties without doing anything about the underlying cause of those difficulties.

When I moved from India back to Tokyo I stumbled across a refugee charity run by a British woman, Jane, with whom I could easily communicate. I asked to go with her the next time she went to a camp, paying all my own costs, and hoping to collaborate on something. Jane agreed and, a few months later, we went to three projects on the Thai border with Myanmar. When we came back, I did an exhibition of my Indian photographs and some of the pictures of this trip. We used the exhibition to raise money for the refugee charity I’d accompanied. We made about $35,000.

Having done that, I then began to understand just what a huge deal the refugee situation is. The more I learnt about it, the more I wanted to try and do something about it and photography seemed like one approach.

At the end of Freefall, there's a letter that my late grandmother sent to me several years ago. My father was born in Italy in 1940, his family were Jewish at a time when it was not a good place to be Jewish. My father and his mother spent some time displaced, basically fleeing through Italy, and several members of his family went to gas chambers. So, I also realised that actually part of my family history had been displacement and so that personalises what is a very important issue for the planet.

You travelled to 20 countries in order to document the effects of war and conflict. How did you decide which countries to go to?

Basically, access is one of the hardest things to achieve, and so to a large extent it was a matter of where I could find situations that I could get to. For example, I took a number of pictures in Egypt because I was connected with a charity in Egypt where I could gain access; or I took some pictures in Turkey, Lebanon and Jordan because I could get there with a charity who could get me into certain places.

But, other times, it's because I happened to be somewhere for reasons like my day job. So I was in Kuala Lumpur or Jakarta or Italy for my finance job but, before going, I did whatever I could to try and find people locally who would be able to connect me with someone I could photograph. In that respect the book is a bit unbalanced because I've got no one from Central America, I’ve got only one picture from the States. I did go out of my way to take some pictures in continental Europe. I think that people misunderstand that the refugee catastrophe is a European problem - it isn’t - but nevertheless, that is part of the story and Europe was under-represented. A lot of the pictures are from Asia because that's where I'm based.

You mentioned Europe, and you travelled to places like Greece, which is host to many UK and European tourists every year. Did you notice anything about this conflicting image of a country whilst travelling?

If you’re asking about the juxtaposition between tourists generally and refugees, no I didn't really spot that. But what I felt very strongly at a personal level was a huge sense of discomfort when I would go and photograph people who were in really quite desperate situations. Then at the end of the day, we were able to get into our vehicles and I was able to wash my hands of the situation and go back to wherever I was sleeping which was normally safe and comfortable.

I think that was something which could feel very challenging because I would basically intrude into people’s lives, ask them to let me photograph them, ask them their stories, and then at the end of it, I could go get a beer somewhere. The only way that I rationalise that to myself is that at least by raising awareness and moreover by raising money out of the project, I'm trying to do something which makes it worth their while. Otherwise, what's the point?

I really hope the pictures in the book are dignified and they're not demeaning people. It is incredibly important they're not making people look like victims. I'm trying to do this partly to help people, and photographing someone in a stage of acute distress is not helping them, so I chose not to

Was there a country that had a particularly lasting effect on you? Why?

There were several pictures there from a place called Marawi, in the Philippines. It is a town which was invaded by ISIS and there was a siege for five months where a lot of people died. Hundreds of thousands of people were displaced and remain displaced.

One of the reasons I went there is because if you photograph refugees, you are generally photographing people where they end up. It was important to me in the book to have some pictures of the origins of displacement, for example war zones - or there are some pictures in the book of people with torture scars or who have been shot or otherwise injured. Marawi was eye-opening because being in a town which has been a warzone is something that most of us luckily don't see. It's a very visually arresting thing and that clearly stays with me.

But I think that the other place which sticks in most in my mind most was Gaziantep in Turkey, near the border with Syria. There was an apartment block there which had over 1000 people in it and hundreds of them were kids. From memory, less than 30 of the kids were actually in education. So literacy levels were receding.

An obvious theme of displacement is loss. Everyone understands that a refugee has lost her or his house, and I think it's quite intuitive they've lost their money. Then of course a lot of the people I've met have lost their loved ones, and I've met a lot of people who have lost limbs. Then in a lot of countries, refugees aren't allowed to work so people lose the ability to support themselves. Along with being able to work is a strong sense of dignity and self-worth, and so there are mental health issues that are associated with not being allowed to be part of the workforce.

But the really staggering thing for me was understanding that families or entire communities were losing literacy, and that will set them back by a generation. There is a large number of Syrians, for example, where the parents can read, but the kids can't read anymore. That will have a generational impact and that sticks in my mind.

Your photo book reveals the sheer scale of the situation of those who have been forcibly displaced worldwide. How can books like yours change the predominantly one-sided rhetoric of media that can often be dehumanising?

I think the media is culpable for more than one thing actually. I agree there's a dehumanising element. There are some things I won't photograph because I don’t think it helps. There is a very deliberate narrative arc in this book which is meant to end with a message of hope: these are not people who need our pity, rather these are people who need assistance, and we just need to find a way to help them realise their potential. So I think that's one thing, to try to pick pictures which send that message - and we designed the book so it starts with the origins of displacement and works through scenes of displacement but finishes with a more optimistic message.

The other thing that the Western media gets utterly wrong is that they portray this as a Western problem, as a European problem. Most photographs that people like you or me would see of refugees involve people in boats in the Mediterranean or people walking across Eastern Europe and that’s nonsense. The vast majority of refugees in the world are living in so-called developing countries elsewhere, there's a huge number in Sub-Saharan Africa, and there are huge numbers in places like Pakistan or Iran or Turkey. That doesn't get seen.

One of the reasons it was important for me to have 20-plus countries in the book is because it was meant to demonstrate that this is so much more than a European issue. There are refugees in Kuala Lumpur, there are refugees outside Jakarta in Indonesia, there are refugees in Hong Kong, there are lots of refugees in different parts of Sub-Saharan Africa, as well as in Cairo, there are many refugees in the Middle East.

I do have some pictures from the UK and from Greece and Paris, but they are a minority. That's partly because of where I could get to, but also because that's actually a fair representation of the world.

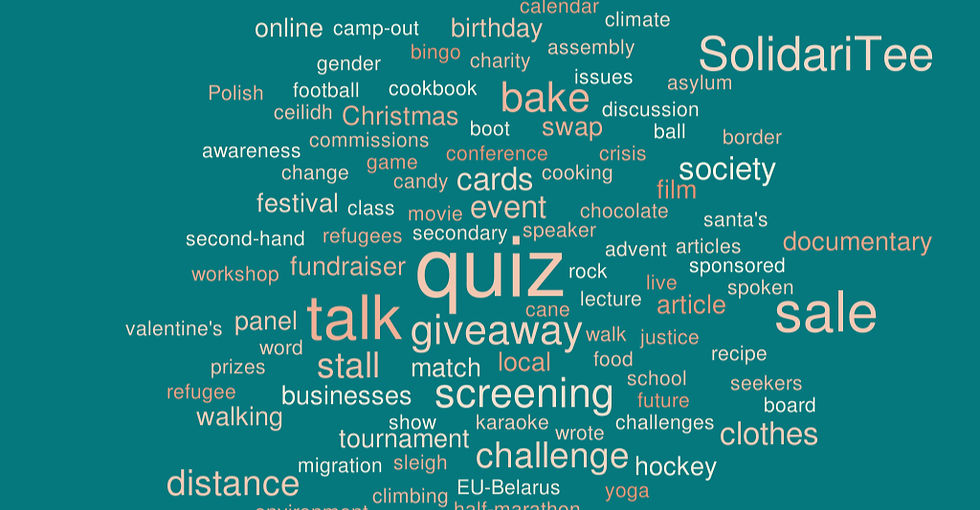

What I'm hoping to do is use these pictures through avenues such as SolidariTee to try to do something to fix the issue that I have documented. I think that photographs can be especially powerful when paired with fundraising because I don't want to take pictures of things without them helping to solve, in whichever tiny way, the issue that I've photographed.

Full amount of profits from Freefall go to SolidariTee through Alexander's generous support.

Comments