Asylum-Seeking and Asylum-Hiding: Challenges and Advances in Legal Aid Provision

- Team SolidariTee

- Nov 18, 2025

- 8 min read

Updated: Nov 26, 2025

In this piece, Irina, a current SolidariTee team member and psychology student, explores how the very nature of the asylum system leads to physical and mental harms for those in need of international protection, and unpacks the context around SolidariTee's focus on supporting organisations to adopt holistic and trauma-informed approaches that ensure legal assistance goes hand-in-hand with mental health support.

“When you try to make an appointment, it is full, you have to go to your container and talk to yourself.”

This statement, made by an asylum-seeker in one of Greece’s reception centres, reflects a shortfall of appropriate and reliable psychological care for people fleeing persecution (Border Violence Monitoring Network, 2025).

The word “container” sticks out; used to describe temporary housing for the displaced, it paints the speaker as an object to be stowed away. Closed Controlled Access Centres are highly monitored and remote reception facilities, in which 60% of people report there being no opportunities to interact with local Greek people. The physical and social isolation induced by reception facilities undoubtedly makes eventual assimilation into Greek society even more difficult (International Rescue Committee, 2021).

Amidst growing anti-immigration sentiments in the media, and authorities’ intent on securing borders further (Alexandridis, 2025; Konstantoupoulou et al., 2022), people making an often-life-threatening journey to Greece must persevere through a range of social, material and emotional challenges to have a chance at obtaining refugee status. A new

understanding of medico-legal partnerships has recently emerged in this context; when the resilience of displaced people rides on their hope for a safer future, human rights practitioners need to not only offer clients pragmatic legal solutions, but also assume a therapeutic role (Malliarou et al., 2021; Micoli, 2022).

The physical and mental toll of displacement

In 2024, the Refugee Support Aegean reported 69,000 applications for asylum in Greece, with more than 7,000 “manifestly unfounded” rejections. This means that, despite having experienced persecution, more than 10% of applicants have been denied the right to asylum, often resulting in detention, destitution, or effective deportation. Contrary to some streams of media, the term ‘refugee crisis’ does not describe an unmanageable number of immigrants in Europe, but insufficient protection offered to the increasing number of displaced people fleeing humanitarian crises from across the globe (Konstantoupoulou et al., 2022).

All people seeking refuge hold the right to an adequate standard of living while their claims are being processed, in line with directive 2013/33/EU and the 1951 Refugee Convention.

For many, however, basic needs remain unmet; according to 80-100% of residents

interviewed across the Closed Controlled Access Centre of Samos and other Greek reception facilities, food is scarce and its quality inadequate, with reports of meals being long expired and even “unfit for animals”. In addition to severe overcrowding and provision of dirty or “recycled” drinking water, both of which can transmit disease, asylum-seekers experience intense stress around the uncertainty of their situation, with some having

insufficient time to prepare for asylum interviews and others waiting months for a response (Border Violence Monitoring Network, 2025; Farhat et al., 2018; Gordon et al, 2021).

Since mental and physical health can influence one another, these living conditions often have detrimental effects to displaced people’s psychological well-being.

Systemic issues in Greece’s asylum-seeking procedures

Due to the country’s location, most asylum-seekers entering Greece are from Sudan, Egypt, or Afghanistan (UNHCR Operational Data Portal, 2024). Understandably, people forced to flee high-conflict areas are more vulnerable to exhaustion, depression and PTSD than the general Greek population (Giannopoulou et al., 2022; Malliarou et al., 2021; Theofandis et al., 2022 World Health Organisation, 2022).

Another harsh reality for asylum-seekers is that just one misinterpreted word can cost an individual their refugee status (Dadhania, 2020). Each of these struggles can interfere with participation in court proceedings, putting individuals at increased risk of unfair rejection if they struggle to discuss their experiences clearly and calmly.

Asylum interviews are lengthy and incredibly personal, with applicants’ safety hinging on their being able to retell traumatising experiences calmly and thoroughly. Highly emotional memories involving oneself, however, tend to be focused on the ‘gist’ and sensation of what happened over the details.

Reference (Haskell & Randall, 2019)

Many asylum-seekers arrive without friends or family who can help corroborate each other’s statements. When legal ‘aid’ providers only push traumatised individuals for details without considering their internal state, for some, refugee status becomes completely out of reach.

According to the 1951 Refugee Convention, a refugee is a person who has fled their home country and been granted protection abroad due to "well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group or political opinion”.

Given that defending one’s own identity is at the core of the asylum-seeking process, it is that, and targeting thereof, which needs to be evidenced in court for a person to be granted refugee status.

This is especially difficult to prove for groups such as religious and sexual minorities, whose fear of persecution can be deemed unfounded if they fail to fit a visual stereotype or otherwise ‘verify’ their belonging to these groups (Basdeki, 2025; Berg & Millbank, 2009; Zisakou, 2021).

If fear has led them to keep these aspects of their lives private, asylum interviews can feel even more invasive. Further still, asylum claims can be viewed with suspicion and dismissed by officials who consider the two elements of identity incompatible (Danisi et al., 2021; Yildiz, 2022).

A person’s perceived credibility, therefore, depends on both their own ability to calmly recall details and the perceiver’s broader acceptance of the speaker, each at odds with real psychological aspects of the forced migration experience.

Cruelly, these are grounds to reject an asylum claim, complicating the path to safety for people with certain life experiences.

A holistic approach to protecting human rights

Since human rights practitioners with limited understanding of asylum-seekers’ resilience, individual identity and mental health status are perhaps less able to prepare clients for the arduous legal process, it is crucial to upskill legal professionals in this area to improve chances of success (Eleftherakos et al., 2018; Micoli, 2022; Pineda & Punsky, 2024).

For human rights lawyers, this would involve not only acknowledging and learning to

work around clients’ potential emotional difficulties, but also recognising their autonomy, identity and active role in the legal process, as outlined by the European Human Rights Advocacy Centre (2022).

The ancient Greek term θεραπεία (Therapeia) broadly means the act of serving and caring for another person. Having been at the forefront of Europe’s refugee crisis since 2015, and faced criticism for its strict legal requirements, it is essential to apply therapeutic approaches, in this sense, to the asylum-seeking process.

The Therapeutic Legal Assistance Model, developed by AMERA International in 2022 in partnership with SolidariTee, outlines methods of directly integrating psychological knowledge and practice into the asylum-seeking legal process. So far, the model has guided holistic legal training sessions for more than 40 human rights practitioners, which has

been organised with the help of student-led fundraising.

About SolidariTee

This article was written as part of an individual initiative for SolidariTee, with the goal of raising awareness of some of the barriers faced by displaced people in Greece, as well as highlighting a novel legal approach to working with asylum-seekers.

SolidariTee is a student-run organisation collaborating with a range of small-to medium-scale Greek NGOs to raise funds for the provision of trauma-informed legal aid, which draws on both human rights principles and psychological evidence.

SolidariTee is currently collaborating with eight non-government organisations to connect thousands of displaced people in Greece with psychological and legal practitioners who provide free and unconditional aid such as counselling and interview preparation.

Some concentrate on advocating for specific vulnerable groups such as women, children, survivors of violence, separated families and people with mental conditions; others focus on research and education, aiming to challenge anti-immigration sentiments. The organisations can be found HERE.

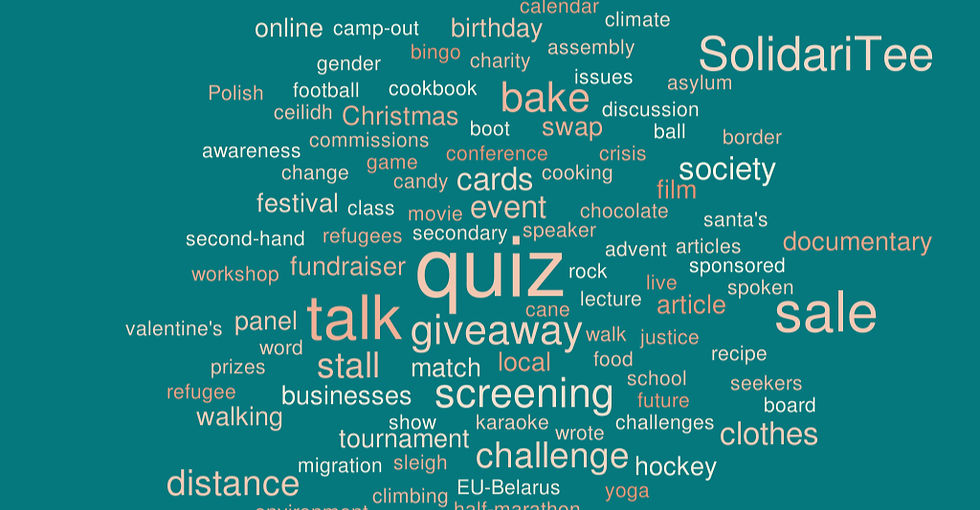

Beyond running events and campaigning against misinformation on social media, members of the team gather funding through t-shirt sales. In October, the Leeds team organised a combined bake/t-shirt sale in the town centre and held a t-shirt stall at the union’s Palestinian Culture Day, encouraging conversation about forced displacement from members of the student population and general public.

For SolidariTee, t-shirts are central to both education and fundraising – one t-shirt costs £10-12, which can pay for a whole day’s rent to keep a small NGO office open; four sales can cover a single trauma-informed legal empowerment session within a refugee camp. Each design centres people with a forced migration background, encompassing themes of hope,

community, culture and individual experience.

This piece was written by Irina Treyster, an Advanced Psychology student at the University of Leeds, and a member of the SolidariTee Leeds team. This piece was also published in the Psynapse magazine connected to the Department of Psychology.

References

Alexandridis, A. (2025). From migration as a social movement to biopolitical control: an analysis of

migration and border management in the eu’s south-eastern border from 2015 until 2024. Vrije Universiteit

Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.5463/thesis.1338

Basdeki, M. (2025). Scripts of Credibility: Discursive Framings and Stereotypes in Queer Asylum Adjudication

in Greece. A Critical Reading through Intersectionality, Temporality, and Orientalism Theory.

Ben Farhat, J., Blanchet, K., Juul Bjertrup, P., Veizis, A., Perrin, C., Coulborn, R. M., Mayaud, P., & Cohuet,

S. (2018). Syrian refugees in Greece: experience with violence, mental health status, and access to information

during the journey and while in Greece. BMC Medicine, 16(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12916-018-1028-4

Berg, L., & Millbank, J. (2009). Constructing the Personal Narratives of Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Asylum

Claimants. Journal of Refugee Studies, 22(2), 195–223. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fep010

Border Violence Monitoring Network. (2025). Violence Within State Borders: Greece.

C Danisi, Dustin, M., Ferreira, N., & Hyde, N. (2021). Queering asylum in Europe: legal and social experiences

of seeking international protection on grounds of sexual orientation and gender identity. Springer.

Dadhania, P. R. (2020). Language Access and Due Process in Asylum Interviews. Denver Law Review.

Eleftherakos, C., van den Boogaard, W., Barry, D., Severy, N., Kotsioni, I., & Roland-Gosselin, L. (2018). “I

prefer dying fast than dying slowly”, how institutional abuse worsens the mental health of stranded Syrian,

Afghan and Congolese migrants on Lesbos Island following the implementation of EU-Turkey deal. Conflict

and Health, 12(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-018-0172-y

European Human Rights Advocacy Centre. (2022). Guide: Trauma informed legal practice for lawyers working

with adult survivors of human rights violations. https://ehrac.org.uk/en_gb/resources/guidelines-for-trauma

informed-legal-practice-for-lawyers-working-with-adult-survivors-of-human-rights-violations/

Giannopoulou, I., Mourloukou, L., Efstathiou, V., Douzenis, A., & Ferentinos, P. (2022). Mental health of

unaccompanied refugee minors in Greece living “in limbo.” Psychiatriki, 33(3).

Gordon, A., O-Brien, C., Balen, J., Duncombe, S. L., Girma, A., & Mitchell, C. (2021). A cross-sectional survey

of sociodemographic characteristics, primary care health needs and living conditions of asylum-seekers living in

a Greek reception centre. Journal of Public Health, 31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-021-01622-x

Haskell, L., & Randall, M. (2019). Impact of Trauma on Adult Sexual Assault Victims: What the Criminal

Justice System Needs to Know. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3417763

International Rescue Committee. (2021). Walling off welcome: New reception facilities in Greece reinforce a

policy of refugee containment and exclusion. https://www.rescue.org/eu/report/walling-welcome-new-reception-

facilities-greece-reinforce-policy-refugee-containment-and

Konstantoupoulou, V.-I., Didymotis, O., & Kouzelis, G. (2022). Covert Prejudice and Discourses of Otherness

During the Refugee Crisis: Α Case Study of the Greek Islands’ Press. Journal of Social and Political

Psychology, 10(1), 173–190. https://doi.org/10.5964/jspp.5633

Maria, M., Dimitra, T., Mary, G., Stella, K., Athanasios, N., & Sarafis, P. (2021). Depression, Resilience and

Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) in Asylum-seeker War Refugees. Mater Sociomed,

Micoli, F. (2022). Human Rights practitioners’ approach to refugees and migrants. A therapeutic psychosocial

perspective.

Operational Data Portal. (2024). Europe Sea Arrivals / Greece. Unhcr.org.

Pineda, L., & Punsky, B. (2022). Mental health as the cornerstone of effective medical-legal partnerships for

asylum-seekers: The terra firma model. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy,

Refugee Support Aegean. (2024). Asylum procedure statistics in Greece 2024: Four in five asylum applications

The UN Refugee Agency. (n.d.). The 1951 Refugee Convention and 1967 Protocol relating to the Status of

Theofanidis, D., Karavasileiadou, S., & Almegewly, W. H. (2022). Post-traumatic stress disorder among Syrian

refugees in Greece. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.911642

World Health Organization. (2022). World report on the health of refugees and

Yildiz, E. (2022). Migrant Sexualities, Queer Travelers: Iranian Bears and the Asylum of Translation in

Turkey. Differences, 33(1), 119–147. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-9735484

Zisakou, S. (2023). Proving gender and sexuality in the (homo)nationalist Greek asylum system:

Credibility, sexual citizenship and the “bogus” sexual other. Sexualities, 28(5-

Comments