Book Review - Exit West by Mohsin Hamid

- Team SolidariTee

- Jan 11

- 12 min read

Updated: Feb 1

Exit West is a book published in 2017 by Mohsin Hamid, the author of a number of other pivotal books including The Reluctant Fundamentalist.

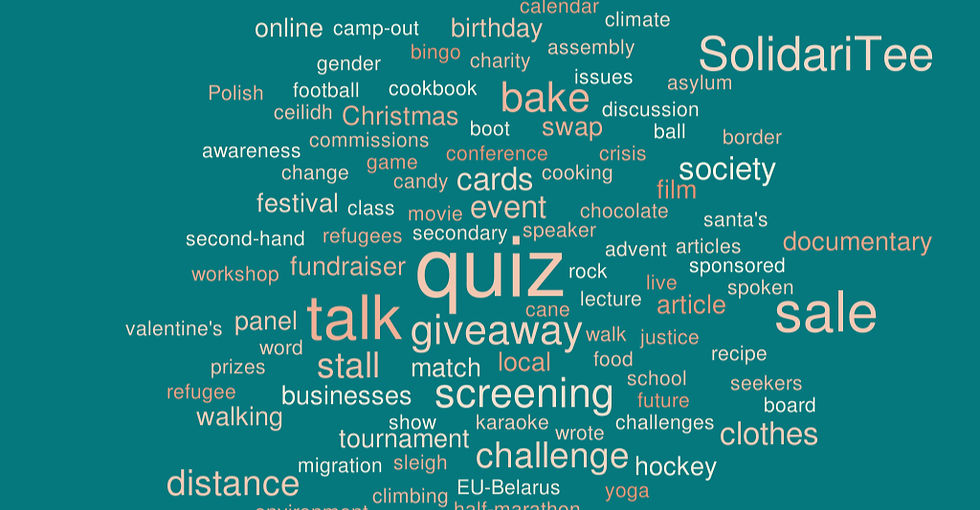

In the 2025/26 academic year, a small group of SolidariTee volunteers have set up an 'asynchronous book club' where instead of everyone being asked to read a book in the same time period ahead of a group discussion, the group voted for a list of titles for everyone to read at their own pace. Once a member has finished a book, they can volunteer to write a review with their reflections, and share their thoughts with the group.

This review has been written by Rebecca (Bex) Kerr, SolidariTee's Networks Coordinator in the current academic year. Bex holds a Masters in International Security and Terrorism, and has written this review as an academic-style piece. In it, she explores concepts connected to the theory of necropolitics, which is a framework describing the political and social power that governs who lives and who dies in today's global landscape.

Introduction

Hamid’s Exit West is set in an unnamed world. The omnipresent narrator calmly tells readers from the start that war will break out soon. From the blurb and front page, we knowingly watch war creep up on the protagonists Saeed and Nadia, who are humanised in the way Hamid tells the tender and restrained story of his only named characters’ love. Aesthetics convey and control temporal violence in Exit West (pace, vignette, forewarned violence), folding the reader into a structure that mirrors the uncertainty of displacement and slow violence. Readers soon stumble across the black doors, an ostensibly utopian representation of safe refugee passages that magically start opening all over the world. We wait for an ending of safety via the magical doors, which don’t come, hindered by its own design.

What structural privilege lies in the Western reader’s participation in this temporal violence? The novel’s narration, magical realism, and anonymity distance the reader from the characters. Like the guard in Bentham's Panopticon (an 18th-century conceptual prison design), the reader is a privileged spectator who watches violence (which I frame with reference to Mbembe’s concept of necropolitics) unfold over time and space, while remaining unseen and free to leave. The reception of Exit West, whether it is recognised as art or not, still reflects a judgement of taste (how Ellison (2001) defines ‘aesthetics’). This is important because, one way or another, readers contribute to the production of ‘the refugee’ as a distinct aesthetic and cultural category. The spectator’s passive consumption risks reproducing the very violence depicted in the novel.

Necropolitics, Literature, and Exit West

Achille Mbembe’s necropolitics (2003; 2019) reframes sovereignty as the power and capacity to dictate who is allowed to live, die, and be more exposed to death. Mbembe argues that the luxuries of rising liberalism and capitalism enjoyed within Western countries were only possible because of the racialised, violent shadow of liberal democracies: through the slave trade, apartheid state, colonialism, and imperialism. States of exception, like the plantation or Gaza’s open-air prison, constitute ‘death worlds’ ruled by lawless hostility and enmity (threat from a fictional enemy). Like Judith Butler’s notion of ‘grievability’ (2009), necropolitics questions who can be considered more disposable than others.

Necropolitics marks a return to critical theory focused on the body, framing death not as an endpoint. Instead, death is a constructed process that begins before biological decline - and continues beyond it, encompassing slow violence, memory, and mourning. Borders, the rise in refugees, and the evolution of weaponry all illustrate that life and death are not equally prioritised (Pasha, 2024; Talbayev, 2024). While Mbembe writes from a post-apartheid West Africa, its application is nonetheless relevant in European and British contexts. The colonial grammar of death is reproduced in the slow violence and living death of waiting, detention centres, racialised police stop-and-searches, and the rhetoric surrounding which lives are worth granting safety.

Exit West presents us with a world of merciless conflict, the racialised human, state surveillance, brutal killings, slow violence, deferrals, states of exception, and states of enmity (fictional enemy). Scholarship has applied a necropolitical lens in Exit West to killing and remote violence (Liaqat, 2021), and the black doors as exposing the global border regime (Bellin, 2022). Bellin (2022) argues that readers are indirectly implicated in global justice. The anonymity within Exit West - of the city and its refugees - produces a form of ‘disorienting empathy’. Namelessness and facelessness sensitise us to our own ethical implications by de-centring the reader’s identity.

Instead, this post centres the reader, exploring the reader’s privilege and surveillance by framing reading itself as a panoptical and necropolitical practice.

Temporal Violence

The novel’s aesthetics (sentence pace, early introduction to violence, black doors, and vignettes) assign the reader a position of privilege. Aesthetics are conceived by Ellison (2001) as a territory within which judgments of taste are elicited. The novel invites readers to participate in the production of meaning. Whether recognised as art or not, a judgment of taste has still been made. Aesthetics therefore, implicate the reader in the violence of the novel, allowing the reader to participate in the novel’s violence while out of harm’s way.

Long passages in Exit West have a longer claim over the attention of the reader, thus their patience. There is a particular passage which aptly conveys the temporal control in delivering violence, necropolitical logics of disposability, and Butler’s grievability. Saeed sees some boys playing football:

‘but then he realised that they were not boys, but teenagers, young men, and they were not playing with a ball but with the severed head of a goat, and he thought, barbarians, but then it dawned upon him that this was the head not of a goat but of a human being, with hair and a beard, and he wanted to believe he was mistaken, that the light was failing and his eyes were playing tricks on him, and that is what he told himself, as he tried not to look again, but something about their expressions left him in little doubt of the truth’ (p. 82).

The football being kicked around is a human head. Butler (2015) says ‘we can see the division of the globe into grievable and ungrievable lives from the perspectives of those who wage war in order to defend the lives of others – even if it means taking those latter lives.’ Sentence length is a crucial aesthetic affecting the reader’s patience. Forced to wait, the reader is tentatively exposed to ‘barbaric’ violence. Truth ‘dawning’ juxtaposes Saeed wanting ‘to believe he was mistaken, that the light was failing’. Violence is illuminated. Saeed can’t look away, but we, as the reader, can, as we close the book. The point is no one can honestly pretend it’s not there. The reality is written across the unnamed footballer's expressions, entrenched in obscurity.

War as an ‘intimate experience’ (Exit West, p. 65) is explored by Zapata (2021) through the crumbling of the quotidian façade (an unremarkable exterior), the gruesome and sudden deaths of Saeed and Nadia’s family, and the blood of Saeed’s neighbour leaking through their ceiling. Yet, there is an asymmetry in the awareness of violence between the reader and the characters. The reader is forewarned of the violence that faces refugees right from the blurb: ‘in a city far away, bombs and assassinations shatter lives every day’. Again, on the front page, ‘in a city swollen by refugees but still mostly at peace, or at least not yet openly at war’ (1). The adjective ‘swollen’ is sickly and unwell, with a heart of pain and heat. It is declared before Nadia and Saeed are aware.

Violence can’t be ignored. Bullets rip through the membrane of each page as the rhythm of the book is often disrupted by angry noises, reminiscent of the creeping violence in the background. In the distance came the ‘sound of automatic gunfire, flat cracks that were not loud and yet carried to them cleanly’ (15). The tone is set from the start: violence is imminent. The paced long sentences involve the reader whose interest and patience are held longer, while consistent onomatopoeic interruptions of words like ‘flat crack’ split the descriptive narrative elsewhere with their sound. This effect brings war as an intimate experience to the reader. As this structure is sustained throughout Exit West, emerging as an increasingly recognisable feature, readers can expect long passages of violence, as when Nadia is assaulted by the man in the crowd (59-60). Such fixed aesthetics attest to the durability of violence, and in turn, the never-ending wait for peace that characterises a refugee’s journey seeking safety. If only there was a way out…

The Cruel Optimism of Magical Doorways

The swollen city opens its pores. Rumours eventually reach Nadia and Saeed, which ‘had begun to circulate of doors that could take you elsewhere, often to places far away, well removed from the death trap of a country’ (p. 69). When Saeed and Nadia become refugees, they use the doors to go to Greece, London, and then to California. In interspersed vignettes, the narrator shows different anonymous migrant and refugee experiences of seeking safety through the doors.

On the one hand, the black doors allow Exit West to ‘avoid the extreme violence usually associated with the journey refugees undertake’ (Zapata, 2021: 768). Existing literature has framed the doors through utopian and dystopian lenses (Westmooreland, 2025); and, a ‘thought experiment about open-border policies, which may undermine or dissolve the nation state’ (Schetrumpf & Wansbrough, 2022: 89-90). On the other hand, as Rojtinnakorn (2021) highlights, there is a contradiction between the space as a platform for movement and freedom, while at the same time a form of confinement that allows violence to operate. This contradiction can be extended by applying Berlant’s (2011) relation of ‘cruel optimism’, meaning when something you desire is an obstacle to your flourishing. The attachment to an unattainable fantasy or object provides the hope to keep it going, but the pursuit itself causes harm, as does a failure to accept reality.

The reader learns about the black doors before Nadia and Saeed, lending to an optimism that the doors could solve their problems. It is soon evident that the doors not only can’t guarantee safety, but they also make the journey harder. The first vignette depicts a man emerging through a black door that has magically opened in a sleeping woman’s bedroom. The scene is disturbingly intimate in its portrayal of minute, mundane details about the sleeping woman. This is a private and thus hostile environment. Physically arduous to climb through, the man ‘wriggled with great effort, his hands gripping either side of the doorway as though pulling himself up against gravity’ (6) and eventually, ‘tendons straining’ (7), ‘with a final push he was through, trembling and sliding to the floor like a newborn foal. He lay still, spent. Tried not to pant. His eyes rolled terribly’ (7). By negotiating borders, the refugee is defined as a legal category rather than a human one. Likewise, compared to a newborn foal, the man is dehumanised, a whole human no more.

Jessica Smartt Gullion defines the vignette as a ‘literary device whose purpose is to place a question in the reader’s mind and to set an emotional tone over the material that is to come’ (2016: 90). A framing of cruel optimism implicates the reader in Exit West. If readers are shown that doors are not adequately safe routes to asylum, will the wait be worth it anyway?

The Panoptic Reader’s Unequal Gaze

Readers of Exit West are connected to the abstractness and anonymity of war by the narrator, together occupying the same position of privilege. The readers witness death and disposable lives ‘far away’ without sharing in it. The fact that the city is unnamed also creates an interesting tension, on one hand universalising the conflict, making it easier to relate to. Bellin (2022) suggests that the ‘namelessness of Nadia and Saeed’s city and the transnational ordinariness of their lifestyles’ prompts the reader to consider that war could happen to them at some point also. As a result, ‘this disorienting, emphatic experience is emphasised by the novel’s ‘delicate balancing of sameness and difference’ (Felski, 2020, p. 107)’ (Bellin, 2022). On the other hand, anonymity might free the reader from any relational responsibility.

Reading can be compared to the Panopticon, Jeremy Bentham's 18th-century prison. In this prison, there is a central guard's tower surrounded by cells which face inward to the guard's tower. Inmates cannot see through the tower and never know if a guard is watching them or not. The possibility of being watched internalises discipline. In Discipline and Punish (1975), Foucault expands on this unequal gaze and internalisation of discipline as a model for how modern states control citizens. Surveillance generates norms. If people believe they are being watched, they internalise the authoritative gaze and self-regulate in line with expected standards.

Framing the act of reading through the Panopticon is both literal and metaphorical. Behind the page, readers resemble the privileged position of the guard. From the guard tower, 'the cells of the periphery are like so many cages, so many small theatres, in which each actor is alone, perfectly individualised and constantly visible' (Foucault). Rather than approaching the journey through the book as one the reader progresses through passage by passage, we could imagine the scenes and vignettes as the Panopticon’s cells, which exist as stationary and immovable before the reader/guard. Just because we read one scene, this doesn’t mean the existence of others has been erased. It exists as a totality. The book and its temporal depictions of violence do not stop-and-start just because the reader turns their gaze from it. Therefore, the movement is that the reader can put the book down and exit the story.

Spectatorship is not innocent and is itself a technology of necropolitical governance. From the outset, the aesthetics of necropolitics in Exit West's text and paratexts are visible to readers. That the reader does not always recognise necropolitics is a part of its design. Necropolitics is deliberately sly. Its survival depends on hiding in plain sight and is something that we, collectively in the West, have been conditioned not to notice. Death is still considered taboo in Western countries. Our desensitisation to necropolitical violence is a core feature of today’s biopolitical control. Nonetheless, readers of Exit West must confront the uncomfortable truth that the literary aesthetics of necropolitics in Exit West implicate readers as spectators of necropolitics.

Conclusion: Producing ‘The Refugee’ and Policing Your Own Witness

To accept the book as a sociological object, we must accept that it is received by people who both recognise it as art and by those who do not (Bourdieu, 1993). Nonetheless, the extent to which readers resonate with the necropolitics or anonymity surrounding the city, the refugees, and militants, speaks to their wider awareness of whose lives are considered of more value today, and turns our attention to those wider forces seemingly with the power to assign this value.

Ironically, when reflecting on the privilege of the reader, it is crucial to avoid over-centring the reader. Within the panoptical metaphor, the agency of refugees is not defined by entrapment in the panopticon’s cell. Framing refugees as being trapped under surveillance is only productive if we linguistically destabilise the power asymmetry too. A way in which the reader can start reflecting on their own surveillance is to look outside of their existing knowledge structures and listen to stories about the refugee from people with lived experience. Humans are sociogenic creatures; we exist by biology and narrative (Fanon, 1952; Wynter, 2015), since it is simply how we speak that we can tell people who we are.

Language used to talk about refugees is merely one method of producing ‘the refugee’ as a distinct cultural and aesthetic category. As this post has asserted, the actual act of reading itself is not an innocent practice. The reader experiences slow violence due to the aesthetics of Exit West, reading on hopeful for a happy ending, which is cruelly unresolved. Readers who do not reflect on their asymmetrical power and spectatorship of the necropolitical arena mirror Western countries that speak with dismay about refugees and victims of war, yet also take little responsibility for them, evidenced by the closing and externalisation of borders. So, I ask you readers, how do you police your own witness?

Bibliography:

Bellin, Stefano. (2022) ‘Disorienting empathy: Reimagining the global border regime through Mohsin Hamid’s Exit West’, Literature Compass, 19/12.

Bentham, Jeremy. (1995). The Panopticon writings. Verso.

Berlant, Lauren. (2011). Cruel optimism / Lauren Berlant. Duke University Press.

Bourdieu, Pierre. (1993). The Field of Cultural Production: Essays on Art and Literature. Columbia University Press.

Butler, Judith. (2009). Frames of war: When is life grievable? Verso.

Butler, Judith. (2015). ‘Judith Butler: Precariousness and Grievability’, Verso Blogs. Available at: https://www.versobooks.com/en-gb/blogs/news/2339-judith-butler-precariousness-and-grievability?srsltid=AfmBOor8eZA3duKgxuqodCsTRcgMJcmuLxv-2pDWGZlzU-MNJ6CvRRiO (Accessed 14/12/25).

Ellison, David. (2001). Ethics and aesthetics in European modernist literature: From the sublime to the uncanny. Cambridge University Press.

Fanon, Frantz. (1952). Black Skin, White Masks. Grove Press.

Felski, Rita. (2020). Hooked: Art and attachment. The University of Chicago Press.

Foucault, Michel. (1977). Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison. Random House Vintage Books.

Foucault, Michel. (2009). The birth of biopolitics: Lectures at the Collège de France 1978–1979. Palgrave.

Hamid, Mohsin. (2017). Exit west. Penguin Books.

Izgil, Tahir. Hamut. (2023). Waiting to be arrested at night: A Uyghur poet's memoir of China's genocide (J. L. Freeman, Trans.). Penguin Press.

Katherine McKittrick, ed. (2015). Sylvia Wynter: on being human as praxis. Duke University Press.

Liaqat, Qurratulaen. (2022) ‘Poetics of Migration Trauma in Mohsin Hamid’s “Exit West”’, English Studies at NBU, 8/1: 141-158.

Mbembe, Achille. (2003). ‘Necropolitics’, Public Culture, 15: 11-40.

Mbembe, Achille. (2019). Necropolitics. Duke University Press.

Pasha, Suraina. ‘Migrant necropolitics in No Man’s Land camps’, Journal of Refugee Studies, 38/2: 401–417.

Pérez Zapata, Beatriz. (2021). ‘Transience and Waiting in Mohsin Hamid’s “Exit West”’, The European Legacy, 26/7–8: 764–774.

Rojtinnakorn, Monthita. (2021) ‘Spatiality, Freedom, and Violence in Mohsin Hamid’s “Exit West”’, Thoughts, 2021-22. https://doi.org/10.58837/CHULA.THTS.2021.1.1

Schetrumpf, Tegan. & Wansbrough, Aleks. (2022) ‘Imagining Utopia Through Communities in Mohsin Hamid’s “Exit West”’, Metacritic Journal, 8/2: 88-107.

Smartt Gullion, Jessica. (2016). Writing Ethnography. SensePublishers.

Talbayev, Edwige Tamalet. (2024). ‘The Residual Migrant: Water Necropolitics and Borderization’, Interventions, 26/1: 21–35.

Westmoreland, Trevor. (2025). ‘Inverting the Coordinates: Place, Dystopia and Utopia in Mohsin Hamid’s “Exit West”’, Journal of Modern Literature, 48/3: 77-93.

The concept of the magical doors in Exit West really highlights the randomness of borders. It makes you realize that safety is often just a lottery of birth. It is not like playing on professor wins casino where the stakes are just money; for Nadia and Saeed, the gamble is for life itself. Reading this review here in London, I feel incredibly privileged. Solidaritee captures that desperation perfectly. It is a stark reminder that we need more empathy, not just walls.